Professor David Howard from York University has been trying to find a scientific explanation for how choral singers achieve that special "sparkle" or "shine" which, according to Edmund Aldhouse, assistant director of music at Ripon Cathedral, distinguishes the best singers from the talented ones.

Professor Howard's hypothesis was that "if we can hear a difference, we should be able to see something that will show us what the acoustic attribute is that means the brain hears it that way." The research was carried out in an anechoic chamber, enabling Howard's team to record only the purest tones without interference from ambient or reflected sound. It revealed that, when the best choral singers flexed their larynxess to achieve that sparkle, certain frequencies of their voices peaked repeatedly, while the other, less talented singers were unable to produce the same effect.

"In our experiments", he explains, "it looks as if that particular 'ring' is happening above the normal speech area, in the region of around 8,000hz." The effect is "something that makes you sit up, it's something that communicates with the soul." According to the BBC, a similar resonance has been found in older opera singers as well, albeit at a lower frequency.

Interesting stuff, I thought, and it made me wonder: why should a frequency above the range of speech make us sit up and take note? What evolutionary purpose could it serve; or did it reflect something else in us, something more ethereal? Beauty, the saying goes, is in the eye of the beholder - but could this ring Howard speaks of and the effect it has on us be an objective, quantifiable example of aural beauty?

History is of course peppered with explanations as to what makes something beautiful and what separates art from the mundane. Seldom, however, have they been put forward by scientists - for aesthetics tends to be the domain of philosophers, poets and artists alone.

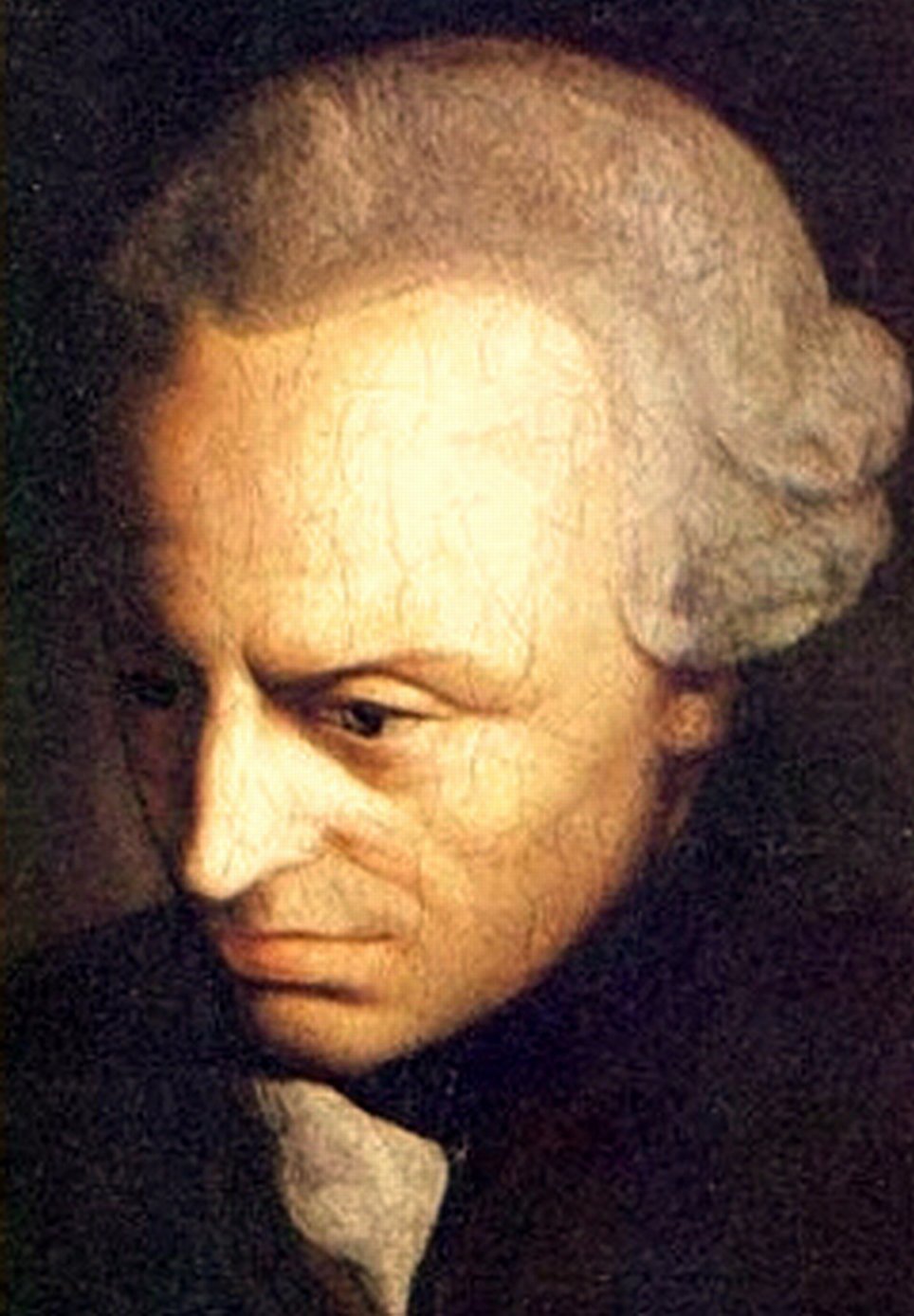

Immannuel Kant, for example, thought that beauty is something exhibited by things with distinct and tangible forms that please our senses: things such as flowers or a sculptures.

Immannuel Kant, for example, thought that beauty is something exhibited by things with distinct and tangible forms that please our senses: things such as flowers or a sculptures.Choral singing, however, would belong to a different category alltogether, namely that of the Sublime, which is what this big brain from Koningsberg called those larger than life experiences that are so wondrous that they inspire awe and are simply beyond our grasp. A good example of attempts to capture this kind of fleeting profundity would be the famous works of J.M. Turner.

I would agree with Kant on this one, and even though many people today see little virtue in classical music, dare I say, they are just plain wrong: there is no aural equivalent to the visceral power of a full choir backed up by a symphony orchestra, no matter how much bass one might peddle.

|

| J.M. Turner - Dutch Boats in a Gale (1801) |

But I digress. We've all no doubt had a sensory experience which overpowered us in such a way that we find it difficult to convey with words. As Kant put it succinctly, the Sublime is something that we "cannot get our heads around." Likewise, the voice that Edmund Aldhouse seeks also defies explanation: it's "just something you know, maybe not something you can define" - which, incidentally, is more than reminiscent of St Augustine's explanation for time.

G.W.F. Hegel, on the other hand, came to the opinion that beauty in art is an expression of our human ideal. Although a work of art expresses the individual who created it, along with the culture that brought him or her up, what makes it art per se as opposed to any other thing is that which makes it timeless; that which relates it to the progress of humanity.

G.W.F. Hegel, on the other hand, came to the opinion that beauty in art is an expression of our human ideal. Although a work of art expresses the individual who created it, along with the culture that brought him or her up, what makes it art per se as opposed to any other thing is that which makes it timeless; that which relates it to the progress of humanity. In this way, Hegel thought that through sculpture, music and painting we are able to transcend our temporal and geographical circumstances and get a glimpse of our Spirit, which was his term for the evolution of human consciousness.

Could, then, the peculiar resonance discovered by Professor Howard be a scientific explanation for what messieurs Kant and Hegel tried to pin down with their respective ideas of the Sublime and the Ideal?

It would, of course, be fascinating to see follow up studies in later centuries so that we could find out whether or not the frequencies change with time, but, leaving that aside, what reason could there be for such a musical threshold that separates mere melody from something more meaningful? Professor Howard is able to provide no real explanation for this, nor can he tell us what his discovery is: "It's way beyond words, it's way beyond the music, it's something about the content going straight from the brain of a singer to the brain of a listener."

Perhaps a poet could help were the scientist fails. In Bards of Passion and of Mirth, John Keats describes the song of a nightingale as "divine melodius truth" - in other words, truth untainted by the blunt instrument of language. Words can easily mislead, while Keats was of the view that melody provides "philosophic numbers smooth" because it does away with words and works therefore at a more immediate level.

Could it be, then, that melody and song are useful in ways we no longer appreciate? Perhaps we are simply too enamoured by our linguistic prowess to recognize the true value of other, more subtle ways of communicating.

It would seem so - at least if the next example is anything to go by. When flying in formation, the FA 18 Hornets of the Blue Angels are often separated by less than a metre. As they perform their death defying manoeuvres - led by the team leader rather than being fully choreographed in advance - at speeds of 500 knots and counting, the team can only be successful if they know what the lead pilot is thinking, when he's thinking it. There is simply not enought time for the team leader to use words for each bit of information, so his team mates need some other connection into his mind in order to act as an undivided, single unit. And melody provides them just that.

The lead pilot communicates with his colleagues by singing out his commands: a low drawn out voice denotes delicate changes to their movement, while a high pitched voice instructs the others of tighter twists and turns. Admittedly, this is just a system they've devised rather than some Vulcan mind meld, but the song of sorts does add a non-linguistic dimension to the team's communication.

Anecdotally at least, this goes to show that instructions laced with melody are superior to words alone. In this particular case, the result is a supersonic harmony without which the jet-powered ballerinas would crash into each other before you could say oops.

In a similar vein to Keats, Paul Johnson opined that song is the high road into the mind of a bird - but the Blue Angels would suggest that this can also apply to us featherless bipedals. Indeed, whatever the reason, a melody sung well can often connect us intimately with its singer, without need for intermediary tools such as words, facial expressions or gestures.

This is because language uses concepts, ideas and relationships to signify and depart meaning, and we have to learn and know its rules, and then collate the whole lot into a message. Singing, on the other hand, is more immediate in how melody can bypass the alphabetical middleman and access our feelings more directly - which is what makes music a truly universal language.

The listener might be wholly ignorant of the rules within music; they can have the musical skills of a cricket, and be as theory-wise as a bat, but they can still hear it, understand it and be affected by it in a most profound and meaningful way. While still the single most useful skill when it comes to survival, language is unable to replicate this feat because it demands too much inside knowledge.

Leonardo wrote that, "in art we are said grandsons unto God." Perhaps he was pointing to the same thing as Hegel, that in art we partake in our shared Spirit. And maybe it could explain what Professor Howard's special resonance is: a key that connects us to each other, and to all humans, from the first to the last.

Whatever the reason behind our fascination with music, one thing is certain, singing, listening and dancing, they make us feel good. I would argue that music doesn't just unlock the dopamines in our brain like chocolate does; that there is a deeper thing going on, of which dopamines are the effect rather than the cause.

Just look at people in a club or at a concert, individuals enjoying life inside the same musical bubble; or how, in action, a symphony orchestra becomes so much more than the sum of its parts; or how an angel choir can order the hairs on our neck to stand up and listen; or how we can understand the singer without having a clue as to what they're saying. On top of all this, music is also able to unify individuals and cultures in ways like no single language can, of which the Eurovision spectacle of 2010 is only one cheesy yet profound example.

In any case, maybe someone like Simon Cowell will one day pind down the je ne sais quoi that gives music its magic, but, until then, I'm content enjoying its fruits. Actually, now that I think of it, I should've just played you That Same Song by The Beach Boys:

This post is dedicated to Paul Johnson - thank you for And Another Thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment